Today’s issue is an excerpt from The Book of Weird Girls, a book about music writing that I’m working on, from which this newsletter takes its name. I debated on whether or not it was appropriate to share a navel-gazing story about my life during these insane and racist times, but ultimately I felt doing so would provide some perspective into my relationship with music and perhaps be relatable to anyone who has ever felt diminished for being sincere. Plus I think it’s a good story and it’s all true, so I hope you find something of value in its telling.

We return to regularly scheduled programming with the next issue of Weird Girls Post, which will be sent on July 3rd, the day of the next Bandcamp Friday fundraiser. It will be focused on artists and labels from West Virginia. Keep an eye out. Horse photo at the bottom, as usual, and a happy surprise.

Thanks for reading.

- MT

The story of how I came to dwell in West Virginia starts outside of Nashville, Tennessee, on a hot August day, in a Ford Explorer going 100 miles an hour down the highway with music blasting over the sound of the wind roaring outside the rolled-down windows.

I’m sitting in the backseat with my great friend, Elle Carroll. Her friends Nate and Sunshine are in the front, chain-smoking cigarettes and picking songs to play off an old iPhone. We’re on the way back to the city from an outing to Rutledge Falls, near to where the Bonnaroo Music Festival is held. I’ve become obsessed with water ever since moving to New York City so I insisted on being taken swimming, even though I never went to the beach at all when I lived in California.

Elle is a music writer, too, a good one. We’re similar in a lot of ways, though I am ten years her senior. We first met in the Bay Area before both suffering individual freak outs that led us to flee San Francisco, her for Nashville and me for New York. When I told her I was coming to Nashville on assignment, she immediately set about preparing an itinerary for my trip that will come to inform the piece I’ve come to write, a feature profile of much-maligned Third Man Records’ artist Olivia Jean. This includes what Elle calls a tour of “what Nashville is selling versus what Nashville really is,” which means drinking in every honky tonk on Broadway during the day and then again at every dive bar in East Nashville at night. Much of our time is spent commiserating over the sorry state of music journalism.

We’re annoyed at what we see as PR garbage being passed off as “journalism,” the weird groupthink amongst music writers that actively suppresses and belittles any dissenting voices, the lack of strong critical viewpoints of any kind, the manufacturing of popularity—the list goes on. Though being a music journalist was my dream from the time I was small, each step up the professional ladder has served only to dull the dream’s shine by causing me to feel even more alienated from an industry that only wants to function as a cool form of advertising with no regard for the health of music as an art form. Nobody actually cares about music, it seems, and caring too much is diminished as corny, pointless, uncool. The baked-in hypocrisy of it all has set me teetering on the edge of an existential depression that is soon to swallow me whole, though I’m able to pretend it’s alright for now, whiskey in one hand and cigarette in the other.

“I’m not special,” Elle says to me, as we complain about another overblown review of a mediocre record that was going to sell regardless of what lies the popular music press peddled in service to their corporate overlords. “Other people feel this way, too.”

I nod in agreement, but underneath I feel differently. No, I actually am special. Haven’t I always felt special? Because music speaks to me. It always has. I hear it in my brain every minute of every day. It shapes my outlook, lights my path, imbues the world with impossible colors. In return, I have tried to write truthfully about the records and bands I loved like family, offering myself up as a conduit for the music that has given my life meaning. Though it seems unbelievably arrogant now, there was a time when I even fancied myself as a protector of sorts, an avenging warrior for the unknown artists of the world. But somewhere between California and New York, I lost my crown of righteousness. Now I languish in forgotten exile, getting drunk in East Nashville, complaining about an industry I cannot change, but also will not leave.

At Rutledge Falls, we scramble down a cliff studded with rocks and boulders to a pool of water so cold you have to jump in—trying to inch your way in is torturous. Civil War battles were fought in this area, and it’s easy to envision boy soldiers crouching behind outcroppings and hidden in the trees, filled with hatred for their countrymen. We spend a few hours at the falls before heading back to Nashville, music blaring the entire time. This is how I find myself in the backseat when, of all songs, the boys choose to play “Take Me Home Country Roads.” It’s instantly familiar—that stomping intro, those silvery harmonies, the pastoral lyrics that make your heart swell with nostalgia for a place you’ve never been. Everyone in the car begins singing.

I never think much about John Denver except when I do. I suppose this goes for everyone. You’re probably singing “Country Roads” to yourself right now. It began to play in your head the very moment you read the title because that’s how it is with a song like “Country Roads” and with an artist like John Denver—a song’s best friend, as they say. Though the modern distaste for anything that smacks of earnestness dictates that we dismiss Denver as corny, there’s no denying that the unvarnished sincerity of his sentiments is a surefire weapon against the posturing of the terminally hip. Nobody wants to be uncool. Nobody wants to be a John Denver fan.

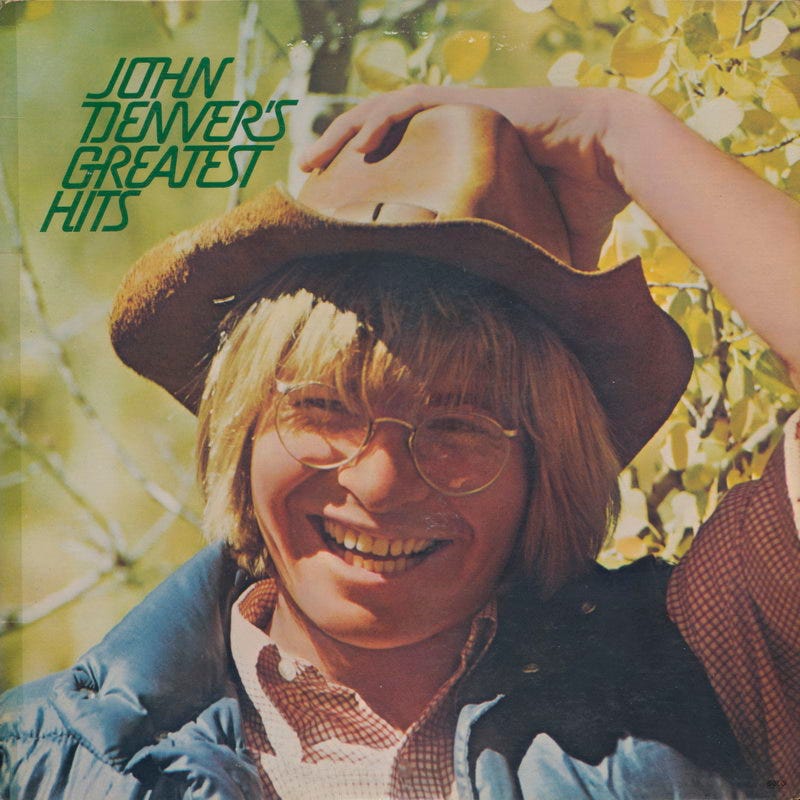

When I was packing up to leave the Bay Area, an experience that proved more emotionally difficult and drawn out than any break-up ever was, I went through my record collection, determined to lighten my load. Once you’ve moved a vinyl collection more than twice, you begin to reconsider how much of it you actually need. Dividing the LPs into piles, I came across the dusty copy of John Denver’s Greatest Hits salvaged from a dollar bin somewhere along the line. It’s been on the chopping block every time I’ve moved, but I could somehow never bring myself to get rid of it. It wasn’t until right then that I understood why.

In the days when I still believed in the unassailability of my own musical taste, I would say that everyone should own a copy of the Pentangle’s first record. I loved Pentangle. I loved the self-titled record. I loved how it mixed jazz and folk, how it sounded timeless but also modern, how the decades couldn’t dim its veneer of cool, its sophistication, and self-possession. Then my best friend— a terrific music writer who is so good at music writing he doesn’t do it anymore because he considers it beneath him—summarily dismissed the record as “white fuckery,” to which I could say exactly nothing. This statement was and is so true that I’ve not really been able to listen to Pentangle since and certainly have stopped recommending it to anyone. Holding the John Denver LP in my hands, Denver’s bespectacled, boyish face grinning goofily at me from the cover, I felt doubly foolish because obviously this is the record that everyone should own. You may not always want to listen to John Denver. You may not ever want to listen to John Denver. But when you do, absolutely nothing else will suffice. Of course John Denver is white fuckery, too, but of a different sort.

“Everyone in country music hates John Denver,” says Sunshine, puffing on a cigarette in the passenger seat as the song comes to a close. I ask why.

“Because he was a rich kid who never saw a country road in his life,” he replies. “But I’m telling you, if you’re in West Virginia, it doesn’t matter if you’re at a gangster party, a frat party, an old person party, whatever. When this song comes on, everyone starts singing.”

A place where everyone sings the same song. I roll the idea over in my mind, remembering what it felt like to belong in a place, connected to a larger community through a shared musical language that crosses all boundaries—basically the opposite of what it feels like to be a music writer in New York City in the year 2019. A place where everyone sings the same song. If such a place still exists, maybe that’s where I need to go.

The day before our trip to Rutledge Falls, I go to the Third Man Records headquarters to interview Olivia Jean. I almost didn’t want to take the assignment initially because neither Olivia Jean nor Third Man are “cool” or “punk,” but my visit to Third Man makes me feel terrible about buying in, even a tiny bit, to the narrative that artists who don’t register on some hierarchy of hipness aren’t worth covering, that somehow my currency with the New York media crowd would be devalued if I deigned to write seriously about someone who has been declared uncool.

Because everyone I meet at Third Man is so genuine and friendly, all of them dressed in yellow and black like a hometown football team. “You gotta,” says one employee when I ask about their unofficial uniform. “We’re like a big band.”

I’m given a tour of the place, which has a recording studio and the photo lab and a performance space and an area where they put together special collectible packages for fans. Everything is done with so much attention to detail and no concern for cost. I’ve never seen anything quite like it, though I’ve spent plenty of time in record stores and recording studios and DIY venues all over the country. I’m touched by the care Third Man puts into everything, which makes me ashamed for having allowed myself to feel too cool for any of it—as if a punk house with 14 roommates and vomit all over the bathroom is somehow a purer expression of love for music than using your own money to repress obscure records because you think people should hear them, because you want to help musicians who never got their due. I’m filled with respect for what Jack White has built.

Jack White doesn’t have to do these things, I tell friends back in New York, but he does them because he truly loves music and wants to help music. And he doesn’t ask for anything in return, he just does it because he loves music. That’s more punk than all the “punks” with their tech money and beer sponsorships running around Brooklyn can say. The comparison grates at me so much that I complain about it to the Lyft driver on the way to the Nashville airport. Of course we are talking about music. All I ever talk about is music. Though he’s a white haired grandpa type, he’s a huge metal fan and tells me about how excited he is about going to see Hammerfell in Atlanta with his sons next month.

“Don’t let those New Yorkers grind you down,” he says to me as I start getting out of the car.

“I won’t,” I promise, grabbing my suitcase from the trunk. Then I lie. “But if they do, I’ll just come back here.”

“We’ll take ya,” he responds.

I immediately want to cry, but it’s more than the kindness of a stranger that has suddenly broken my heart. It’s that the empty, disconnected feeling I’ve been avoiding through work and alcohol has come washing back like a tidal wave. I don’t belong, I don’t belong, I don’t belong. Not in Nashville. Not in New York, either. I don’t belong anywhere. Not anymore. The last place I belonged was Los Angeles, when I wrote about music for free and walked down Sunset Boulevard in the golden light of a benevolent sun, a friend on every corner and a show every night. But those days are gone.

The Nashville airport is nearly empty on this early Saturday afternoon. It takes no time at all to get through security so I dawdle in the gift shop to kill time and buy a postcard with a smiling cowgirl on it holding a guitar and the words “Music City” written underneath in curly yellow script. I sit in the terminal and stare at it. Music city. Music world. Music life. Is this it? Is this all there is? Maybe the only place I truly belong is in music. After all, music is what has led me here and this is where I am. There’s no other world to be in. In this moment, in yet another airport in another city I don’t live in, I find that I’ve lost the will to keep moving pieces around on a game board with no rulebook. I’m done negotiating with the universe. I give up the ghost. What other choice do I have? Music is the only human thing in this world I could never hate and the only relationship I ever cared enough to maintain, and so it is the only one I have left. A penitent in a lonely world, I ask music what will become of me. Tell me what to do. Tell where to go. Where do I belong?

And it answers. It always answers.

A snippet from “This Protector,” the final track off the White Stripes’ White Blood Cells, a record I loved at 20, floods my senses. I always liked this song, especially, because Meg sang on it, the Whites duetting about hearing fearful, indistinct sounds coming through the floorboards over creaky, banged-out piano chords. The song’s bridge repeats over and over again in my head: “300 people living out in West Virginia/ Have no idea of all these thoughts that lie within ya/ But now.”

But now.

SURPRISE! NEW HORSE!!

Surprise! Say hello to Scooter, the newest equine citizen of Fort Pet, who arrived home from Georgia last Friday. He is a gorgeous buttermilk buckskin quarter horse and just as sweet as pie. I can’t wait to pet him more and maybe ride him, too. More photos of this beautiful horse surely to come.

this is beautiful. it took me awhile to get used to your style, Mariana, because it's so direct, honest and confrontational it seems a way rawer than almost any modern music writing I encounter, but once I realized how effective it is in communicating the myriad thoughts that overflow your paragraphs without making it seem like it's all too much (and how perfectly it works with the ideas you pour into your writing), I was sold. what you write about is very important and honest and humane and clearly comes from a very real annoyance and hate towards he obviously evil shit that poisons the industry/industries, which is like should be. I'll be waiting for your book.

Perfect!